On the Catalan Referendum and Digital Rights

Declaration by Free Knowledge Institute about the recent events in Catalonia.

Whether or not one agrees with the possibility of independence of a region within Europe, we consider that fundamental rights were breached in the brutal crackdown of the Catalan Referendum.

- FKI strongly rejects the physical violence applied by the Spanish State to peaceful voters in Catalonia during the #CatalanReferendum on 1st October.

- FKI strongly rejects the censorship applied to Catalan people, governmental institutions, organisations and companies, such as the intervention to their bank accounts - requiring authorisation by the Spanish government for payments of public money -, interception of postal mail, opening of envelopes, confiscation of political pamphlets, prohibition of political assemblies, arrest of political leaders and directors of democratic institutions, threatening and applying huge fines to individual leaders who didn't submit to abide by the Spanish Constitution.

- FKI strongly rejects the Internet censorship methods used, taking down or restricting access to hundreds of webs, applying unacceptable Internet filtering techniques through the main ISPs (Telefonica, Vodafone, Orange), demanding the collaboration of Amazon and Google to take down voting and referendum related apps (which they did - shame on them!)[1]. It is urgent to defend the freedoms and rights in the digital age.

- FKI considers that this can't be dealt with by zero offers of dialogue (from Madrid) and full repression by the Spanish State, breaching fundamental rights under the pretext of breaking the constitutional article on the "Unity of Spain". Democracy and universal human rights are fundamental and above such article.

Brief facts

- 2006: Catalan and Spanish parliaments aporove a new Statute for Autonomy for Catalonia.

- 2010: the Spanish Constitutional Court accepts the rejection by the Partido Polupar and invalidates important parts of the new Statute.

- 2014: a referendum is prepared for 9 November but is declared unconstitutional and is converted into a non-binding popular consultation.

- 2015: elections for the Catalan parliament are advanced to prepare a binding referendum, and a (small) pro-independence majority takes the parliament

- 2017: the Catalan parliament prepares and celebrates its referendum on 1 October, despite being unconstitutional, but based in the referendum law of the Catalan parliament. See: international delegation of observers, background on Wikipedia.

Self-organisation and the use of distributed technologies

Despite the blockade by the Spanish State, both the Catalan government and a massive popular movement -a movement that has taken the streets every 11 September (the Catalan national day) for the last 6 years-, continued their preparations. When the Spanish police intercepted millions of #1Oct pamphlets, people shared them online in PDF for self-printing, putting them on the streets, see collection at Wikipedia. When they confiscated the ballots, people also printed them, just in case there weren't any available to vote with on Sunday.

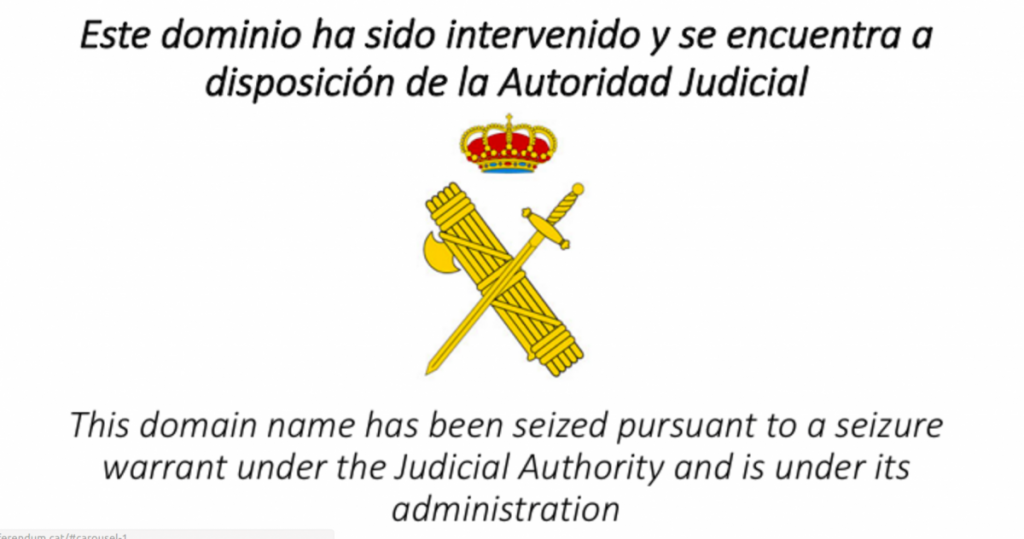

When the referendum website (referendum.cat) was taken down, the scenario had been foreseen, replicas started to appear. People mirrored the code on github, collectively improving the site. By the end of September the database where citizens could vote was made available on that site, and mobile apps were made available to check, in a secure way, where to vote. Google was requested to take down such app from its store and complied. As did Amazon. Meanwhile the big Telecom operators providing ADSL and mobile Internet started to apply Internet filtering, a technique that is disapproved of by the global Internet community. With this filtering, the selected websites cannot be reached through these operators. However when connecting through the net from other countries, one bypasses these Spanish filters. A so called VPN connection allows it and some people started using such services to connect to the net, from outside Spain.

Also a distributed app was launched at IPFS.io. This is a distributed file system and application server. If you install the IPFS app on your computer, no central app store is needed and censorship risk is minimised, unless the .io domain name (in the UK) would have to be taken down but, even then, copies of that network could emerge (see more). For non-technical people, solidarity networks were in place, and in many places people and social movements helped others to find the right location where to vote.

Despite the blockade by the Spanish State, both the Catalan government and a massive popular movement -a movement that has taken the streets every 11 September (the Catalan national day) for the last 6 years-, continued their preparations. When the Spanish police intercepted millions of #1Oct pamphlets, people shared them online in PDF for self-printing, putting them on the streets, see collection at Wikipedia. When they confiscated the ballots, people also printed them, just in case there weren't any available to vote with on Sunday.

When the referendum website (referendum.cat) was taken down, the scenario had been foreseen, replicas started to appear. People mirrored the code on github, collectively improving the site. By the end of September the database where citizens could vote was made available on that site, and mobile apps were made available to check, in a secure way, where to vote. Google was requested to take down such app from its store and complied. As did Amazon. Meanwhile the big Telecom operators providing ADSL and mobile Internet started to apply Internet filtering, a technique that is disapproved of by the global Internet community. With this filtering, the selected websites cannot be reached through these operators. However when connecting through the net from other countries, one bypasses these Spanish filters. A so called VPN connection allows it and some people started using such services to connect to the net, from outside Spain.

Also a distributed app was launched at IPFS.io. This is a distributed file system and application server. If you install the IPFS app on your computer, no central app store is needed and censorship risk is minimised, unless the .io domain name (in the UK) would have to be taken down but, even then, copies of that network could emerge (see more). For non-technical people, solidarity networks were in place, and in many places people and social movements helped others to find the right location where to vote.

Days before the outlawed referendum would take place, the Spanish State tried various strategies to assure it wouldn't happen. First, they gave, through the mainstream media, a discourse of illegality and strict application of the law (as they saw it), and criminalisation of Catalan political leaders. Second, through their intent to put the Catalan police under the orders of the brother of the Constitutional Court's president - which only worked out partially. Third, through their strategy to lockdown all schools and polling locations 48 hours before the voting would take place. The reaction was massive and at more than 1000 schools open-days and sleep-overs were organised for the weekend and people safeguarded their polling location. Their right to vote was at stake. On Sunday, early morning, hundreds of citizens joined the polling locations to assure they would stay open and to protect the voting process. The ballot boxes, through a distributed social network, had been secretly stored in the homes of thousands of people who would bring them to the voting locations just before opening, avoiding confiscation. People shared their food and Internet connection, and spent the day in and around the voting. At least two million people did so. Probably, not everyone who wanted to take part in the polls, could do so. The ballot boxes were, some times, hidden by their custodians -when the police came in- to later continue the voting after they left. The voting app to check whether people had voted already was blocked during the first couple of hours but it later appeared under other IP addresses (why was IPFS not used for this?) The Internet connection at the voting locations had been switched down centrally, but people used their smart phones and neighbors opened their home wifi connection. The whole voting process, however well prepared to comply with all legal standards, wasn't allowed to be so. Even in these terrible conditions, some 2.200.000 of the cast votes were safeguarded (i.e. those not confiscated), of which 90% were favourable to the question "Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic?".

Citizens continue to actively using social networks to keep each other informed of the next steps. It is worthwhile to point out that Whatsapp and Telegram networks are monitored by government agencies, while Signal provides better protection through auditable end-to-end encryption. None of these apps works when the ISP's take down the Internet. A growing number of people installed the FireChat app (warning: non-free), that works from mobile to mobile, a p2p app that can work with just Wifi and Bluetooth also when the mobile network isn't working. This app was designed for emergency situations like earthquakes, but has shown to be helpful also in extreme cases of Internet censorship (see the X-net howto).

To denounce and protest against the brutal police intervention, Catalans held a general strike on 3rd October, which was massively followed, roads and main streets were blocked and huge, peaceful demonstrations took cities and villages.

Days before the outlawed referendum would take place, the Spanish State tried various strategies to assure it wouldn't happen. First, they gave, through the mainstream media, a discourse of illegality and strict application of the law (as they saw it), and criminalisation of Catalan political leaders. Second, through their intent to put the Catalan police under the orders of the brother of the Constitutional Court's president - which only worked out partially. Third, through their strategy to lockdown all schools and polling locations 48 hours before the voting would take place. The reaction was massive and at more than 1000 schools open-days and sleep-overs were organised for the weekend and people safeguarded their polling location. Their right to vote was at stake. On Sunday, early morning, hundreds of citizens joined the polling locations to assure they would stay open and to protect the voting process. The ballot boxes, through a distributed social network, had been secretly stored in the homes of thousands of people who would bring them to the voting locations just before opening, avoiding confiscation. People shared their food and Internet connection, and spent the day in and around the voting. At least two million people did so. Probably, not everyone who wanted to take part in the polls, could do so. The ballot boxes were, some times, hidden by their custodians -when the police came in- to later continue the voting after they left. The voting app to check whether people had voted already was blocked during the first couple of hours but it later appeared under other IP addresses (why was IPFS not used for this?) The Internet connection at the voting locations had been switched down centrally, but people used their smart phones and neighbors opened their home wifi connection. The whole voting process, however well prepared to comply with all legal standards, wasn't allowed to be so. Even in these terrible conditions, some 2.200.000 of the cast votes were safeguarded (i.e. those not confiscated), of which 90% were favourable to the question "Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic?".

Citizens continue to actively using social networks to keep each other informed of the next steps. It is worthwhile to point out that Whatsapp and Telegram networks are monitored by government agencies, while Signal provides better protection through auditable end-to-end encryption. None of these apps works when the ISP's take down the Internet. A growing number of people installed the FireChat app (warning: non-free), that works from mobile to mobile, a p2p app that can work with just Wifi and Bluetooth also when the mobile network isn't working. This app was designed for emergency situations like earthquakes, but has shown to be helpful also in extreme cases of Internet censorship (see the X-net howto).

To denounce and protest against the brutal police intervention, Catalans held a general strike on 3rd October, which was massively followed, roads and main streets were blocked and huge, peaceful demonstrations took cities and villages.

Police violence

The Spanish National Police and Guardia Civil (military police) entered Catalonia by thousands (at least 10.000) with the instructions to assure the referendum to become ineffective. However their violent methods included hitting people on the head, throwing them to the ground, breaking fingers, using rubber bullets (which are forbidden in Catalonia). Around 900 injured were reported by the Catalan hospital service. Given the declarations of the Spanish King - with no word on the police violence nor any opening for dialogue - more State violence is expected. The visiting members of the Guardia Civil remain in Catalonia.About the Free Knowledge Institute

The Free Knowledge Institute (FKI) is a non-profit organisation that fosters equal access to tools for production and exchange of knowledge in all areas of society. Inspired by the Free Software movement, the FKI promotes freedom of use, modification, copying and distribution of knowledge in several different but closely related fields. Accordingly, it promotes the commons economy. It has a distributed team in Amsterdam, Rome and Barcelona. The Barcelona team has been witnessing the Catalan process and Referendum from different locations. We consider it our duty to speak out on this.References

- The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) analyses the used filtering techniques for at least 25 blocked sites

- Internet Society statement on Internet blocking measures in Catalonia, Spain

- EFF declaration: .cat Domain a Casualty in Catalonian Independence Crackdown

- X-net Basic Howto for preserving fundamental rights on the Internet

- RT.com: Assange accuses Spain of conducting worlds first internet war to shut down Catalan referendum