On Big Tech Oligarchs and the Transition to Sovereignty

Photo Julia Demaree Nikhinson / Reuters

Photo Julia Demaree Nikhinson / Reuters

A great many people are increasingly concerned about how Big Tech is governing an ever-larger part of our society—especially now that Trump has taken office with his cabinet of 13 billionaires. We could talk about how dramatic our current technological dependence on large North American tech companies is. And about how we got here. But just as importantly: what can we do about it? More and more people are wondering how they can break free from these toxic, addictive, and manipulative apps and platforms, and what alternatives exist. In short, we’re in big trouble with Big Tech. Twitter became a platform for lies, misinformation, and political manipulation. Years before, Facebook had already specialised in this, helping to secure the election victory of Trump I and Brexit via Cambridge Analytica.

Most governments are dependent on Microsoft, and if Trump decides so, their system can be shut down. The word sanctions is crucial here: once you’re on the US sanctions list, your access is cut off as US companies are not allowed to provides services any longer. This is how the Russian-owned Amsterdam Trade Bank went bankrupt when it was sanctioned in 2022 and could no longer access its systems. Since January 2025, this same threat has been hanging over the International Criminal Court, which is entirely reliant on Microsoft’s cloud. The announced sanctions could mean a death sentence for the court.

Back in the 1990s, we had a beautiful vision of how the internet could lead us to a freer world—one where we could interact directly with others, without intermediaries or centralised platforms. We could email, share messages, set up websites, and tell our stories to the world. We could exchange files peer-to-peer, all without dependence on intermediaries. By now, we know that was utopian wishful thinking, held by a small group of tech activists—myself included.

The vast majority found it far more convenient to use tech platforms to search, email, share files, navigate, watch videos, send short messages, and chat. These companies offered those services for free and made their money by profiling us—knowing our behaviour in minute detail and allowing advertisers to target our weakest spots, increasingly manipulating what we read, think, buy, and vote. Over the past 25 years, these tech platforms have become the world’s largest and most powerful companies—we started calling them Big Tech, until they grew even bigger than Big Oil. A century ago, Standard Oil, the world’s largest and most powerful energy company, was broken up. But we failed to do the same with Big Tech. By now, they are not just “too big to fail”—they may be too big to break up at all.

Regulation and Compliance In Europe, we have a series of regulations designed to rein in tech platforms, from privacy legislation (GDPR) to the Digital Markets Act, the Digital Services Act, and the AI Act. These laws empower the European Commission to compel these enormous companies to respect the rights of European citizens, governments, and businesses. However, compliance with these European laws remains limited—due to political will, the constrained resources of regulatory bodies, and the vast lobbying, economic, and marketing power of these corporations. This challenge will become even greater now that the White House is fully backing “their” major platforms. We see Trump and JD Vance proclaiming that the EU was founded to destroy the USA. Ultimately, this is all part of a geopolitical chess game, in which Von der Leyen’s team is under immense pressure to let Big Tech have its way, enabling even greater concentrations of power.

Building Decentralised, Open-Source Infrastructure Enforcing regulations and imposing sanctions is certainly important. At the same time, and in parallel, we must invest—at all levels, but especially at the EU level—in urgently developing and strengthening alternative systems. These alternatives must be decentralised, interoperable, privacy-respecting by design, and open-source. While open-source is not a magical solution, it is a prerequisite for efficient collaboration in the further development of existing alternatives and to prevent a mere switch from American Big Tech to European Big Tech.

Fortunately, there is now significant attention on sovereignty and the reindustrialisation of Europe, as highlighted in the Draghi Report. More specifically, regarding technological sovereignty, the EuroStack report— coordinated by Francesca Bria, commissioned by the Bertelsmann Foundation—focuses on building and strengthening the European tech industry across various sectors, such as cloud services, the Internet of Things, connectivity, and Data Commons, all based on the aforementioned values and principles.

Another set of policy proposals has come from the Barcelona-based citizen platform Xnet, coordinated by Simona Levi and commissioned by the former president of the European Parliament, David Sassoli. The Proposal for a Democratic and Sovereign Digitalisation of Europe advocates for the sovereign development of essential communication tools, including email, chat services, browsers, and cloud infrastructure. They emphasise public procurement policies that prioritise European small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with strict requirements for open-source solutions and open standards. This ensures collaboration, reuse, and vendor independence. (See my review).

Both policy proposals align with the digital commons approach, where the internet is built by communities of producers and users, with a strong focus on shared ownership and democratic governance. A key component of these efforts is the establishment of one or more Sovereign Tech Funds, a mechanism for public and collective investment in the development and reinforcement of digital commons. Germany has already set up such a fund, while France has various government programmes who work in this direction, such as the Digital Transition programme (DINUM). In line, multiple European countries have joined forces in an international organisation dedicated to funding and strengthening digital commons.

A Better Internet Starts with You The third pillar of this transition lies with users 1—and we are all users, from citizens to politicians, from journalists to educators, business professionals, civil society members, and government officials. One of the internet’s greatest strengths was—and still is—its ability to connect users with one another. The more people participate, the more valuable the network becomes - the network effect. Initially, this worked to everyone’s advantage, as the internet was built on open standards that allowed people to communicate peer-to-peer without centralised owners. However, with the rise of Big Tech’s “social networks”—WhatsApp, Instagram, X/Twitter, YouTube, TikTok—we have become trapped within the platforms of single corporate owners. Worse still, we cannot even exchange messages between different apps or platforms. This is why they are referred to as walled gardens or silos.

Fortunately, the Decentralised Internet Never Stopped The movement for a decentralised internet never stopped, and steady progress has been made towards a world of open-source applications that allow people to communicate freely. Take Signal as an alternative to WhatsApp: this chat application is developed as open source by the Signal Foundation, a non-profit organisation that primarily relies on donations from its users. However, Signal is still a US-based non-profit and remains subject to political pressure.

We also have the decentralised chat protocol Matrix (matrix.org), implemented by more than a dozen apps, including Element.io. While Element is technically a for-profit company, it was founded by the creators of the Matrix protocol with the goal of offering a flagship product based on that technology 2. Government ministries in France and Germany use it due to its strong security, sovereignty, and suitability for public procurement. While its decentralised nature makes it somewhat more complex, it is a more sustainable long-term solution. Many online communities have therefore adopted Matrix (matrix.org).

A Brief Overview of Alternatives to Major Big Tech Social Media Apps

| **Centralised or Extractive Platform ** | Decentralised Alternatives |

|---|---|

| Whatsapp, Telegram | Signal, matrix/Element.io, Delta.chat |

| Twitter/X | Fediverse: Mastodon, Lemmy |

| Fediverse: PixelFed | |

| Youtube | Fediverse: PeerTube |

| Fediverse: Friendica, Hubzilla | |

| TikTok | Fediverse: Loops (under development) |

| Meetup, EventBrite | Fediverse: Mobilizon |

| Gmail, Live!/Hotmail, Yahoo | Tutanota, Proton, Posteo, Mailbox, Murena, Soverin |

| Google Drive, Microsoft OneDrive & Teams | NextCloud (with cooperative services e.g. by CommonsCloud.coop, Framasoft, …) |

| Forms | FramaForms, LiberaForms, LimeSurvey |

| Plan a date / Availability poll | Framadate, Rally.co |

| Zoom | Jitsi, BigBlueButton (cooperative service by meet.coop) |

| Amazon | Buy from local shops and platforms |

The Transition: Moving to a Better Network Together Switching from your current network to another is always a challenge, especially because of the network effect, which keeps people on dominant platforms. Transitioning to a new network is difficult, but it is easier when done collectively. This is exactly what groups of individuals and organisations have been doing in recent mass migrations from Twitter/X to Mastodon or Bluesky 3. Through online campaigns, people become aware of the need for change, and groups coordinate their moves at set times4. The process generally involves the following steps -slightly adapted for each specific social network migration:

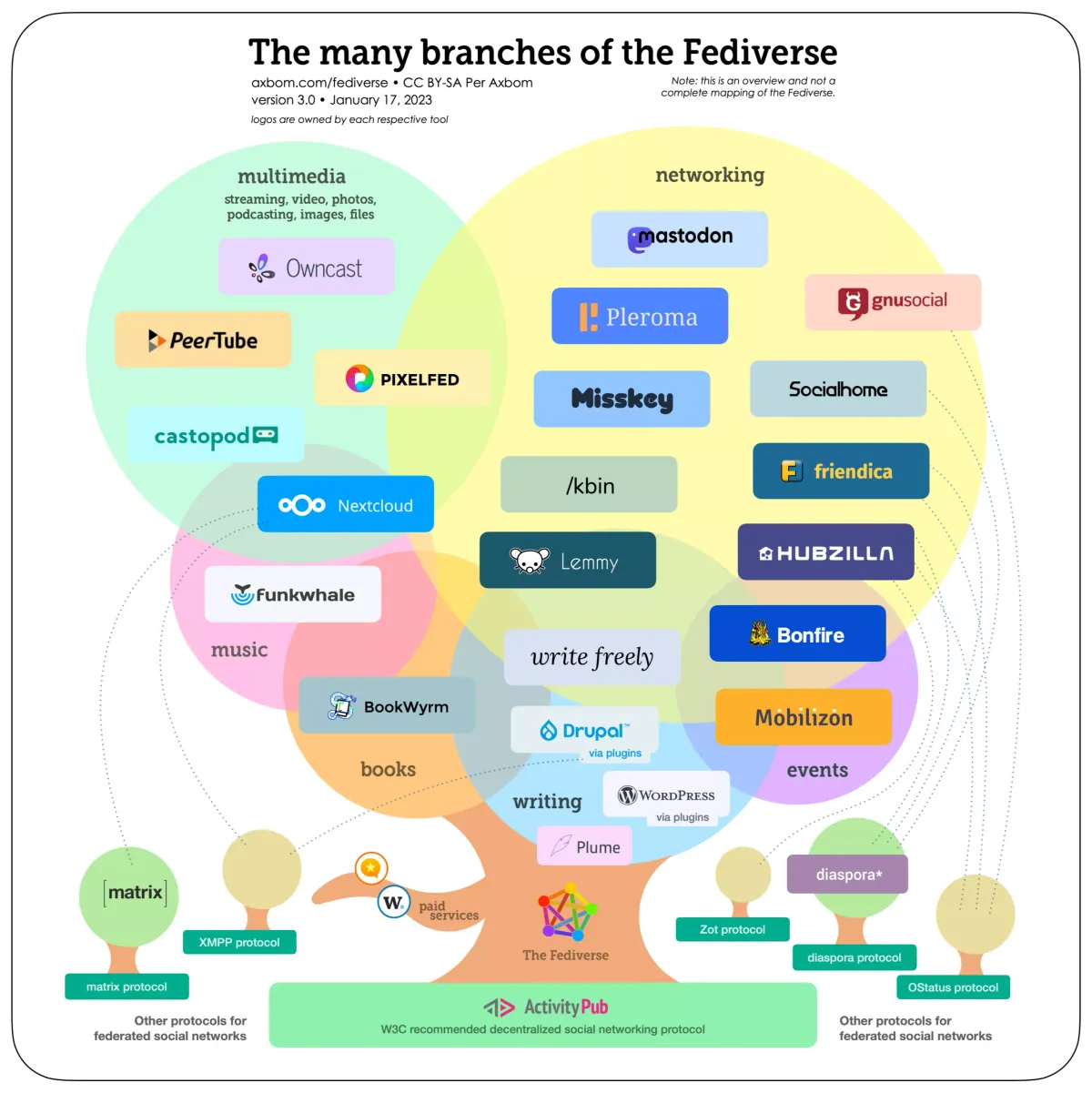

- Becoming aware of the problems with toxic tech and the existence of more ethical alternatives, such as the Fediverse (which includes Mastodon).

- Choosing a server (referred to as an instance in Fediverse terminology).

- Creating an account.

- Either deleting or making your old account inactive: first download your content and post a farewell message explaining why you’re leaving and where people can find you. Tip for Whatsapp: activate an autoresponder e.g. WAmatic.

- Inviting your network to reconnect on the new platform—bring your community with you. Tip for X: use the OpenPortability.org service to migrate your tweets to the Fediverse and help you reconnect.

- Discovering new connections in your new digital space.

- Enjoying the absence of intrusive algorithms, ads, spam, and online abuse. If abuse does occur, you can flag it, block the perpetrator, and your server administrator can blacklist the offender or even their entire server. This process demonstrates how content moderation can work effectively while keeping extremists at bay. The transition requires effort, patience, and persistence. Of course, the Fediverse experience is not always as seamless as that of Big Tech apps, which are developed with billions in cash. But as the network grows, so does the quality of the experience.

The Benefits of Decentralised Social Networks

- No disruptive algorithms steering your content consumption.

- Minimal to no hate speech due to community-driven moderation.

- Ownership and control over your own communication server and identity.

- Maximum connectivity through interoperability: the decentralised nature of the Fediverse means that different networks can communicate with each other. Unlike Big Tech’s walled gardens, Fediverse platforms are interconnected—PeerTube video servers link with Mastodon and PixelFed servers, while Friendica and Hubzilla are connected networks. A book review on Bookwyrm can be shared with a Mastodon follower, and a PixelFed photo album can be discussed in a PeerTube talk show—all across independently owned servers in different countries. This new world has been in the making for over 15 years. It’s not perfect, nor utopian, but it offers a way out—a path to autonomy and sovereignty. Are we ready to take the leap, or will we remain stuck in the comfort of Big Tech’s grip?

Connect with me:

- Fediverse: @wtebbens@social.coop (mastodon), @wtebbens@commoni.fi) (hubzilla)

- Matrix: @wtebbens:one.ems.host

Notes:

-

Note that the word “user” is also used in the context of substance addiction. Here, we (of course) refer to a person who uses a particular service or app. However, a user of Big Tech takes on a double meaning when we consider that these apps are often designed to be addictive, keeping people engaged for as long as possible. ↩

-

Note that the alternatives do not make money through advertisements or user manipulation. Decent tech operates on a fairer business model, where memberships and donations often play a key role. In this model, revenue is primarily intended to cover the costs of the people doing the work, rather than generating profits for capitalist owners. ↩

-

Bluesky was started by the founder of Twitter, and although they currently use relatively friendly algorithms, this is no guarantee for the future. If you look at the investors backing it, it is expected that they will need to generate significant returns, which will likely lead to an extractivist business model. ↩

-

For example, #MakeSocialsSocialAgain, VamonosJuntas.org, and Escape-X.org, which focus on the transition from X to Mastodon. See also the broader French campaign for a “de-Googled internet”: https://degooglisons-internet.org. ↩